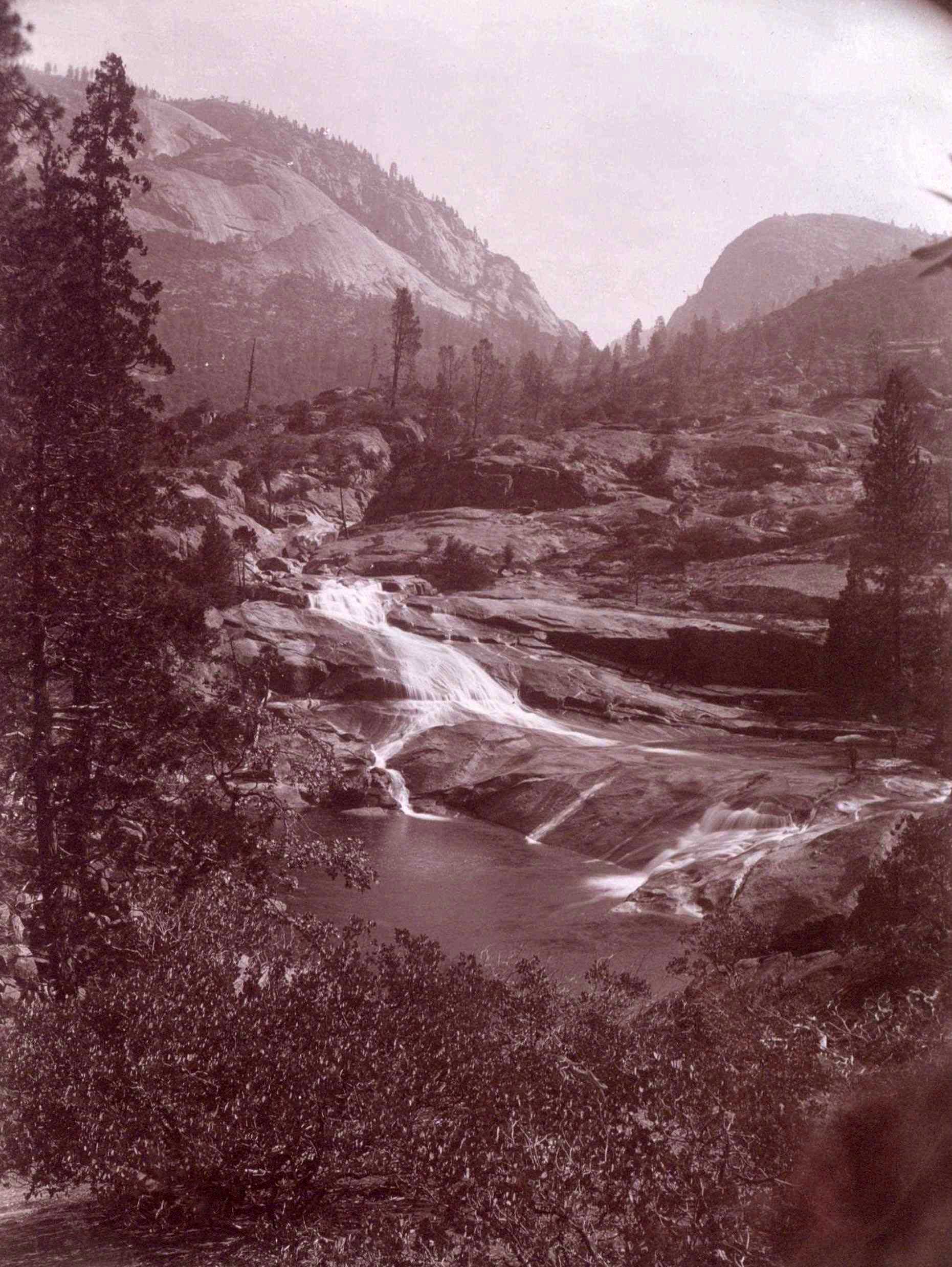

Hetch Hetchy Valley. Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library.

Hetch Hetchy Valley. Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library.

Hetch Hetchy Valley, 1908. Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library.

Hetch Hetchy Valley, 1908. Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library.

The earthquake and fire of 1906 brought San Francisco’s issue of water supply to the forefront. The city’s water and gas lines were broken and shattered by the earthquake. Leaking, flammable gas and a lack of water to fight ensuing fires had created an inferno of massive proportions. Without the water to even attempt to fight the fires, feelings of indescribable helplessness spread through San Franciscans as the flames climbed higher.

These feelings caused many townspeople to blame the Spring Valley Water Company, which held a monopoly on water distribution to the city. This private company had beaten out its competitors, and its purchase price had remained too high for the city’s repeated attempts to buy it out. The Spring Valley Water Company alone shouldered the burden of providing water to the city, which caused it to shoulder much of the blame for the firestorm.

The city planners preferred a supply much more than adequate in the aftermath; they wanted a supply that could serve the city through a century of projected growth. Many of these corporate supplies were not capable of expanding their output enough to match the future population San Francisco strove for. They looked eastward to the clear mountain rivers of the Sierra Nevada range, their upper watersheds yet to be tamed by man. San Francisco Mayor James Phelan had himself applied for water rights as a private citizen, to prevent the rights being bought out from under the city by private concerns. His reasoning was that a private individual or concern could act much more quickly than the slow-moving wheels of government bureaucracy.

Phelan instructed City Engineer Carl Grunsky to investigate potential water sources to satisfy future demands.

Hetch Hetchy Valley. Courtesy of the University of California, Riverside.

Hetch Hetchy Valley. Courtesy of the University of California, Riverside.

From 1900 to 1901, Grunsky, along with his future successor Marsden Manson, found that out of the 14 potential supplies surveyed by San Francisco engineering teams, one stood out: the Hetch Hetchy Valley, with the Tuolumne River flowing through it. Creating a reservoir at Hetch Hetchy, according to Grunsky, would allow for the highest capacity reservoir system with the highest supply of water, at the highest quality. This all came at the lowest relative cost, due to a lack of prior claims on the land. As an additional bonus, building a dam at Hetch Hetchy’s elevation and location provided ample opportunity to develop hydroelectric power. Municipal electricity had not been a large concern through most of the 1800s, but became a priority in urban development by the early 1900s. Compared to buying out private claims and previously developed systems, Hetch Hetchy looked like the solution to San Francisco’s water woes. In late 1901, Phelan applied for water and reservoir rights at Hetch Hetchy as a private citizen, giving these rights to the city by 1903.

Raker Bill

The controversy spilt over into public life with people such as John Muir and even women’s clubs opposing the dam. The discussion continued over the next five years until 1913. Introduced by Congressman John Raker (D-CA), H.R. 7207, also known as the Raker Bill and the Hetch Hetchy Bill, granted San Francisco the right to dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley within Yosemite National Park. The House passed the bill with little debate. The Senate, however, debated the measure extensively before passing the legislation on December 6, 1913. President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill into law on December 19. As part of the agreement to allow the construction of a dam at Hetch Hetchy, San Francisco was required to provide water and electricity to the public. While the water from Hetch Hetchy was distributed municipally, as planned and expected, the electrical power was a different story. From San Francisco’s side, they had run out of money to complete the power distribution network from Hetch Hetchy, and were forced to allow Pacific Gas & Electric (a private company) to distribute. To some, this seemed like a betrayal, and many wondered if San Francisco had planned to build a power network of their own to begin with. This issue was litigated multiple times in the succeeding decades after power initially flowed from Hetch Hetchy, without a satisfactory outcome. Electrical power from the O’Shaughnessy Dam is still distributed by P. G. & E., under an agreement that legally satisfies the requirements of the Raker Bill.

Horseback riders in Hetch Hetchy Valley. Courtesy of the University of California, Riverside.

Horseback riders in Hetch Hetchy Valley. Courtesy of the University of California, Riverside.