John Muir

John Muir first visited Yosemite in 1868 and fell in love with the area, writing that

None can escape its charms. Its natural beauty cleans and warms like a fire, and you will be willing to stay forever in one place like a tree.

He advocated for the protection of the area for over a decade before San Francisco first applied for water rights in 1901. Muir, in collaboration with Century magazine editor Robert Underwood Johnson, was instrumental in Yosemite National Park’s establishment in 1890. After Congress passed the Raker Act granting San Francisco the right to flood Hetch-Hetchy, Muir receded from political life. Less than a year after the Raker Act was passed, on Christmas Eve in 1914, John Muir passed away from pneumonia surrounded by family.

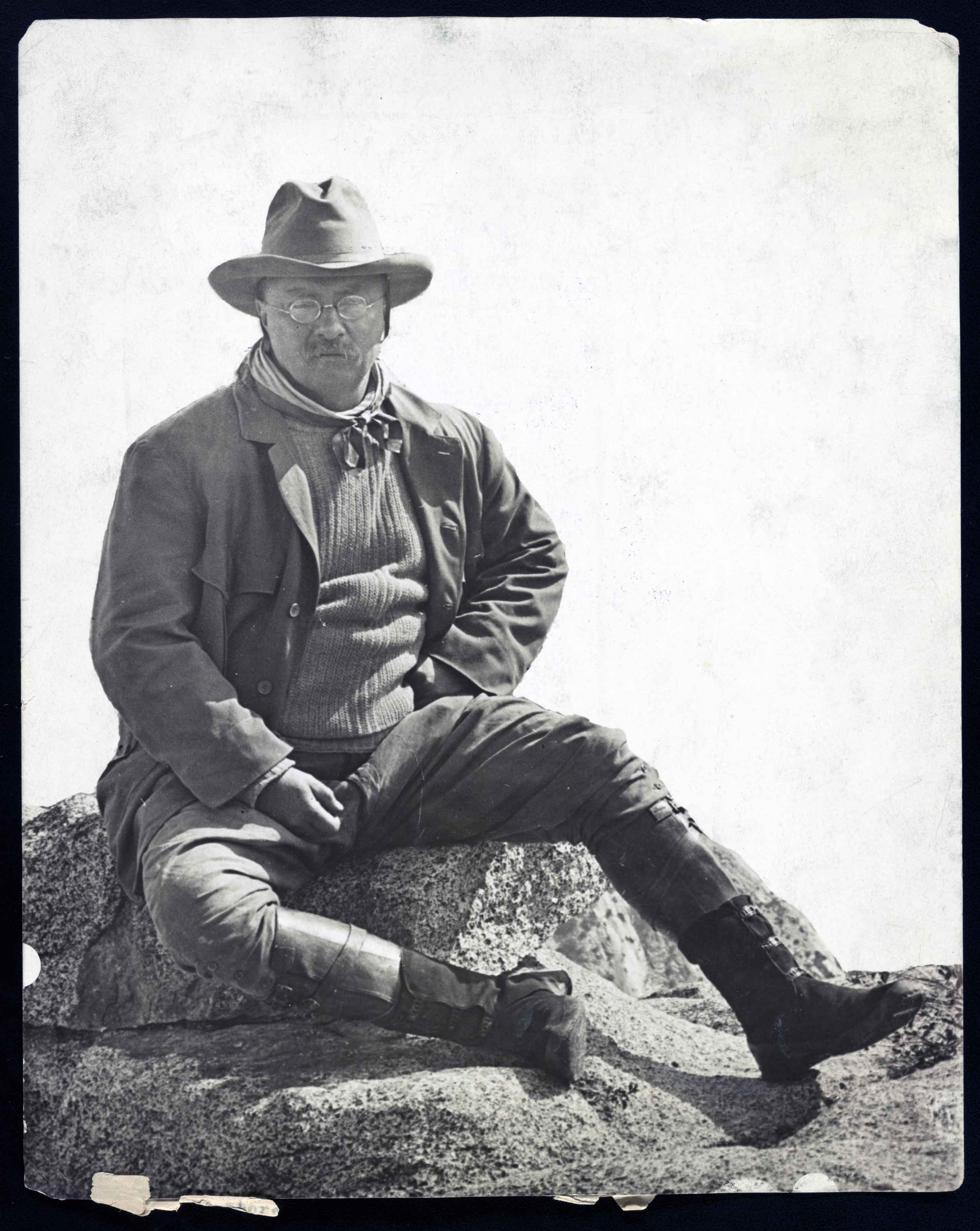

John Muir seated on a rock with a lake and trees in the background. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

John Muir seated on a rock with a lake and trees in the background. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

James D. Phelan

James Duval Phelan was the Mayor of San Francisco from 1897 to 1901 before becoming a U.S. Senator in 1915. Phelan was a driving force for the damming of Hetch-Hetchy. In 1901, Mayor Phelan applied for water rights to Hetch-Hetchy as a private citizen and then transferred the application to the City of San Francisco on their second application in 1903. He returned to public service after the 1906 earthquake and fire as president of the San Francisco Relief and Red Cross Funds, distributing funds to residents affected by the disaster. Although he left office in 1901, he was still closely involved in the fight for Hetch-Hetchy. He wrote articles and spoke publicly in favor of the dam. He testified in legal proceedings on behalf of the city and had considerable influence with government officials and businessmen.

James D. Phelan. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

James D. Phelan. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Teddy Roosevelt

Teddy Roosevelt in Yosemite. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Teddy Roosevelt in Yosemite. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

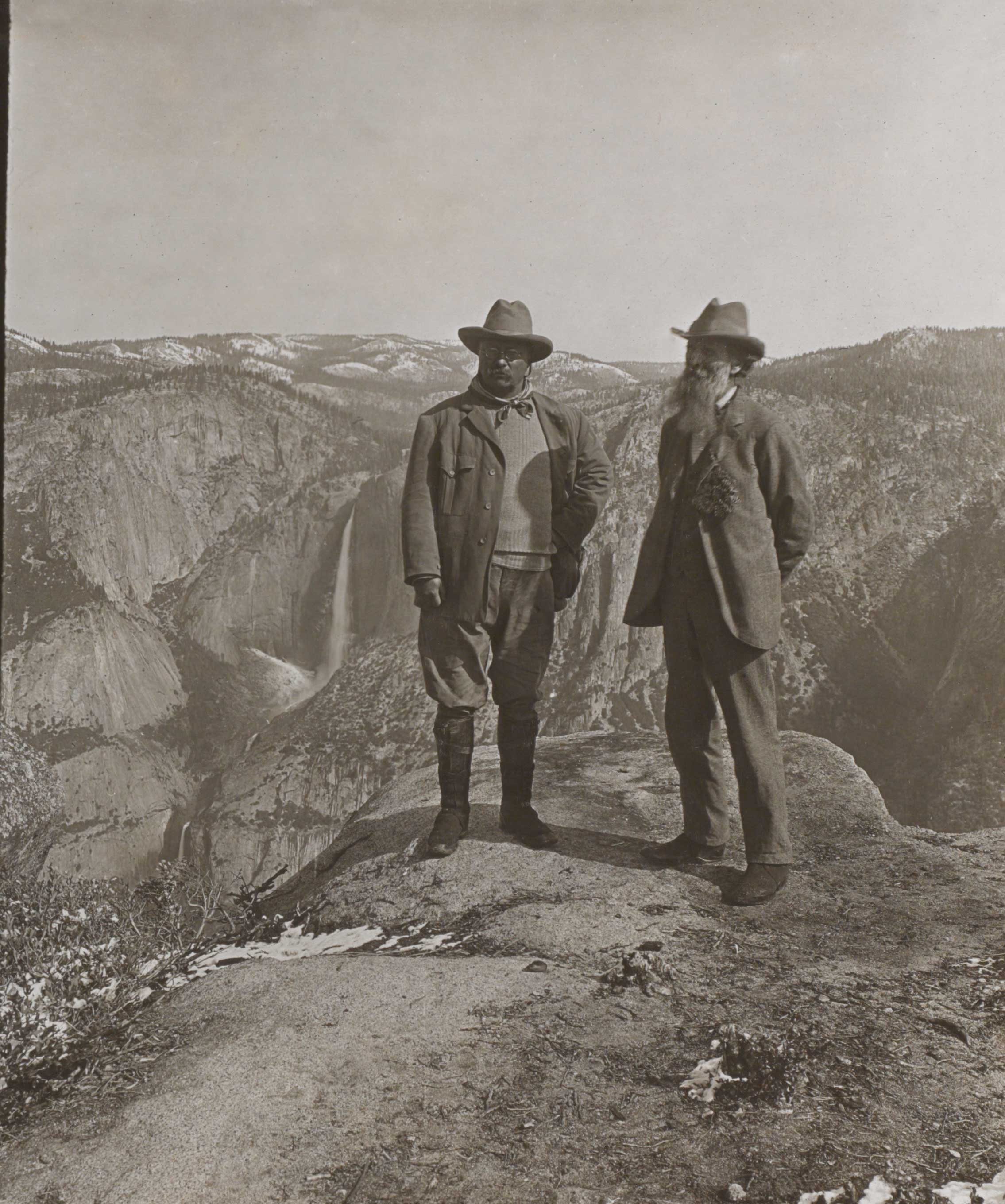

On March 14, 1903, President Roosevelt wrote a letter to John Muir after reading some of his articles and asked Muir to personally guide him through Yosemite, stating “I do not want anyone with me but you, and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.” Muir accepted the offer because he believed President Roosevelt could help push legislation that would protect the area. When Roosevelt arrived for the trip in May of 1903, he sent all his men back to town and continued on with Muir. The President chose to forgo staying at the Wawona hotel and instead camped with Muir in the Mariposa Grove and at Glacier Point, where the President woke up covered in snow.

Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir in Yosemite. Courtesy of the

Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir in Yosemite. Courtesy of theLibrary of Congress.

They bonded over their love of nature and shared stories. Muir discussed his desire for the lands of the Yosemite Grant to be returned to the federal government and added to Yosemite National Park because of the continuing destruction from livestock, logging, and commercial developments; despite California’s management of the area.

Three years later in 1906, in large part due to his camping trip with John Muir, President Roosevelt oversaw the recession of the Yosemite Grant lands from California and their addition to the larger Yosemite National Park.